Understanding “Business Logic” in Software Development

Why This Term Exists

If you’ve spent any time reading about software architecture or browsing codebases, you’ve probably run into the phrase “business logic.” At first it can sound like corporate jargon. Why do programmers need to talk about business at all? Aren’t we just writing code?

The term was coined because as software became more complex, developers realized they were mixing together two very different kinds of code:

The code that expresses the rules of the problem domain — for example, when to charge sales tax, how to calculate an insurance premium, or what counts as a valid move in a game.

The code that handles technical plumbing — such as saving to a database, drawing user interfaces, or sending email.

When these two are all mixed up, the software becomes brittle. If the company changes a pricing rule, you have to dig through the UI layer or database scripts to find and update it. That’s hard to maintain and test.

Developers started using the phrase “business logic” to mean “the part of the program that encodes the actual rules of the business or domain.” Separating it from other logic makes software easier to maintain, test, and evolve.

What Business Logic Really Is

Business logic is the code that determines how the system behaves in its domain. It’s about rules, decisions, and policies. Examples in different domains:

E-commerce:

Applying discounts to a shopping cart

Calculating shipping costs

Enforcing a limit on how many items can be bought at once

Banking:

Determining whether a transaction is allowed

Calculating monthly interest

Approving or rejecting a loan application

Healthcare:

Deciding whether a patient qualifies for a specific treatment

Enforcing privacy and access restrictions

Video games:

Rules for combat, scoring, leveling up

You can think of business logic as “the part of the program that would need to change if the policies or rules of the business changed.”

What Business Logic Is Not

Equally important is knowing what business logic is not. It does not include the technical details of how you present data or persist it. Common examples of non-business (infrastructure or technical) logic:

Drawing buttons, forms, or web pages (UI)

Saving and loading records from a database

Logging information

Sending emails or push notifications

Parsing or serializing JSON or XML

Authenticating users

These tasks are crucial, but they’re not about the rules of the business. We often call this infrastructure logic or sometimes plumbing code.

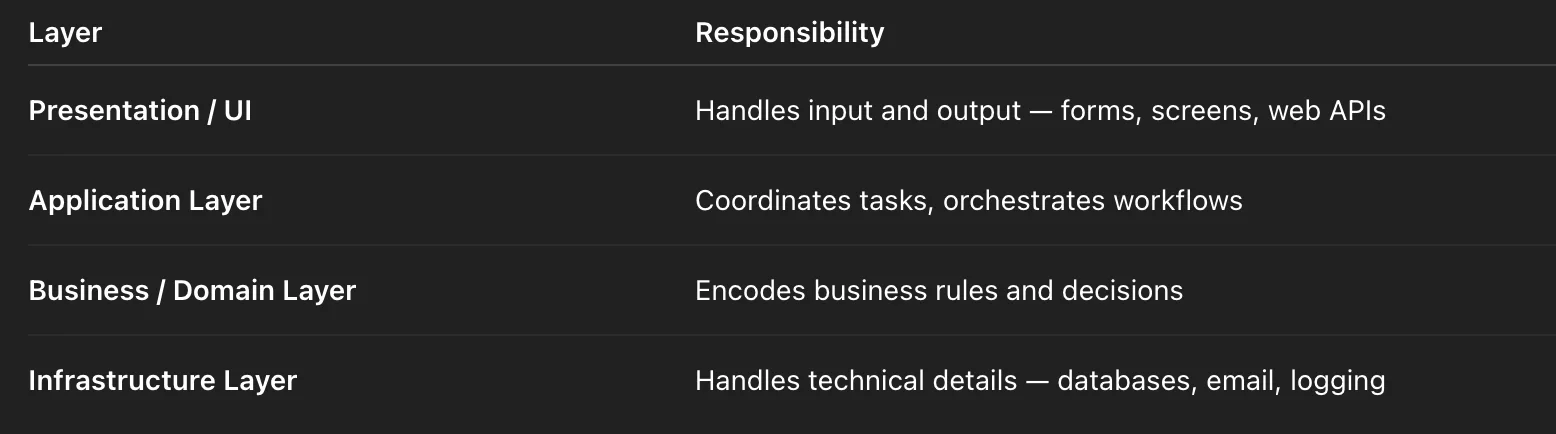

A Typical Layered Architecture

Most modern applications are structured in layers to keep these responsibilities separate:

The major layers of modern systems

This separation allows you to change the UI (say, from a desktop app to a web app) without touching the rules for tax calculation or discount eligibility. Or you can switch from one database technology to another without rewriting your business rules.

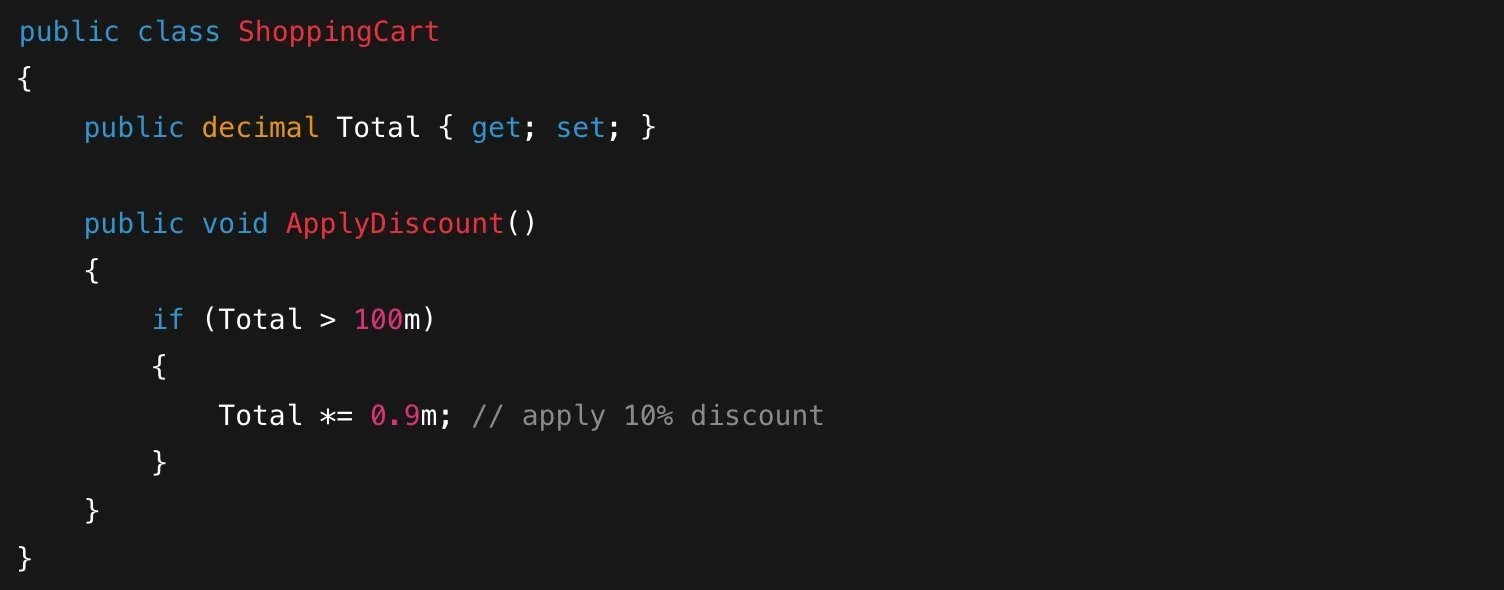

A Simple Example in C#

Let’s imagine we’re building part of an e-commerce system. Here’s some business logic:

The “m” after the numerical values indicates that the value is a Decimal type, as opposed to double or float

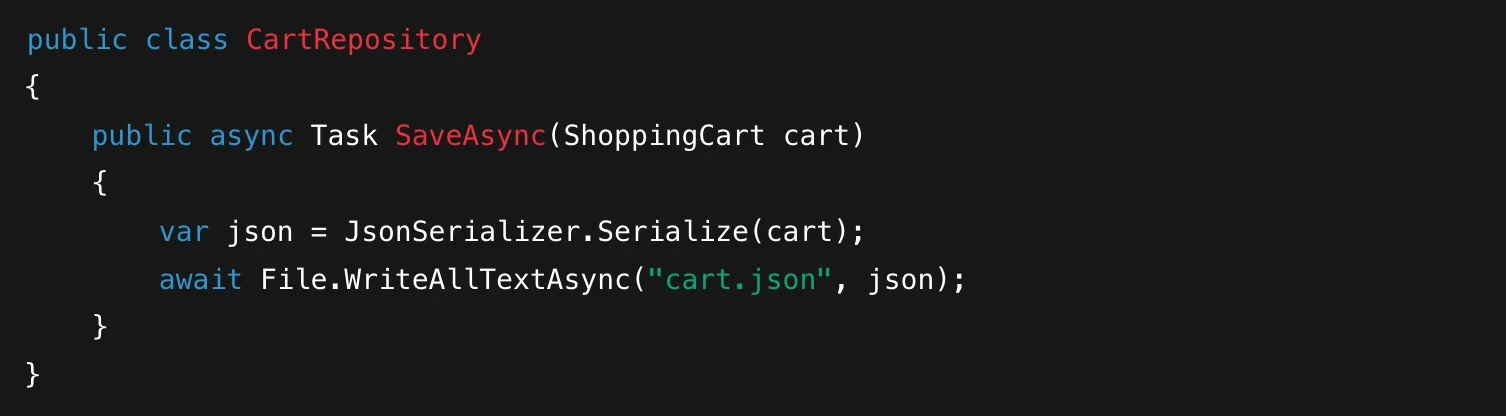

This method expresses a rule of the business: “If the total is over 100, apply a 10% discount.” Now compare that to infrastructure code that persists the cart:

This logic is about how cart data is persisted. The means/technology used has nothing to do with how the business runs. The tech could be swapped out.

The repository cares about where and how the data is stored. If tomorrow the business decides to change the discount rule from 10% to 15%, you’ll only modify ApplyDiscount() — the business logic — and not touch the repository.

Historical Note: Why the Term Emerged

In the early days of enterprise software, it was common to write all the decision-making code directly in the UI layer or in database stored procedures. When the business changed its policies, updating the software was painful because the rules were scattered all over. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, as software teams embraced 3-tier architecture and later domain-driven design (DDD), they began to emphasize keeping the business logic in its own clear layer.

This separation meant:

You could change policies without breaking the UI

You could test business rules without a running database or web server

You could reuse the same rules in different contexts (e.g., desktop and mobile apps)

The phrase “business logic” stuck because it highlights that this code reflects the logic of the business or domain, not the logic of the technology.

Business Logic vs Application Logic

Sometimes you’ll also hear about “application logic.”

Business logic encodes the rules of the domain.

Application logic is the glue that connects infrastructure and business rules — things like workflows, orchestrating tasks, handling user input.

For example, in an e-commerce checkout:

The application logic might validate the form, create an order, and call a shipping service.

The business logic decides how much tax to apply and when to allow free shipping.

Understanding this distinction helps you design more maintainable systems.

Guidelines for Identifying Business Logic

When you’re reading or writing code and want to know whether something belongs in the business layer, ask yourself:

“If the company’s rules or policies changed tomorrow, would this piece of code need to change?”

If the answer is yes, it’s likely business logic. If it’s more about how the program interacts with hardware, storage, or networks, it’s infrastructure logic.

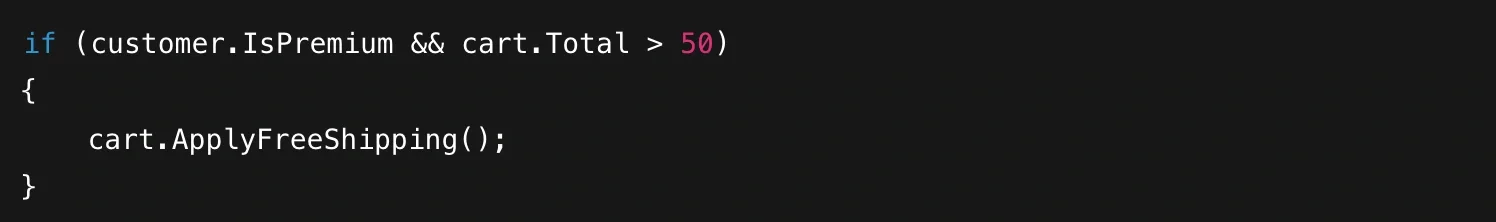

A Side-by-Side Look

Business logic:

The logic pertains to the rules of your business, that you give free shipping to premium customers who spend over $50

Infrastructure logic:

The email service isn’t part of the business- you could swap it out without altering how the business works

The first is about a business decision. The second is about how to technically deliver a message.

Why Separation Matters

Keeping business logic separate from technical concerns brings real benefits:

Testability:

You can write unit tests for business rules without setting up databases or web servers.Maintainability:

Business rules often change; keeping them isolated means less risk of breaking unrelated code.Reusability:

The same core rules can be reused in a web app, a mobile app, or a batch processing system.Flexibility:

You can swap out databases or messaging systems without touching business rules.

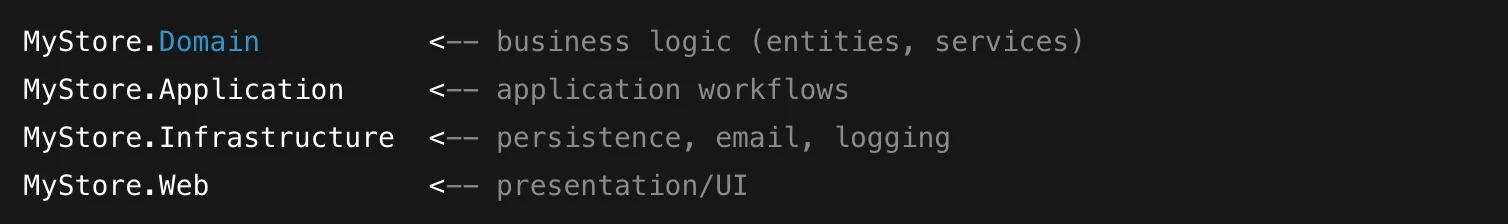

C# Project Structure Example

A typical .NET solution that respects this separation might have projects like:

Common structure of projects

Here, the domain project contains your core rules — the heart of the software. The other projects handle delivery and technical details.

Common Pitfalls

Mixing concerns: Writing database calls directly inside methods that apply discounts.

Business logic hidden in UI code: e.g., validating rules in button click handlers.

Tightly coupling to infrastructure: e.g., calculating prices directly in SQL queries.

Over-engineering: For very small apps, elaborate layering can be overkill — but understanding the principle still helps.

Bringing It All Together

Business logic isn’t about “business people” vs “technical people.” It’s simply about putting the rules of your application’s domain in a clear, dedicated place.

When you know the difference:

You can reason about your program more easily.

You can adapt faster when requirements change.

You write code that’s easier for others (and future you) to maintain.

Final Thoughts

The term “business logic” came about to highlight what really matters in most software: the logic that reflects the policies, decisions, and rules of the domain you’re building for. Everything else — databases, frameworks, user interfaces — is there to support those rules. By keeping the two separate, you give your software a strong foundation that can stand the test of changing requirements and evolving technology.