Mastering the using Statement and IDisposable in C#

Why This Topic Matters

If you’ve ever opened a file, connected to a database, or worked with a network stream in C#, you’ve probably seen code wrapped in a using statement. For many beginners, using looks like a small piece of syntax you copy from examples without much thought. But behind that simple word is an important system that helps your programs run smoothly and avoid subtle bugs.

C# and .NET include automatic memory management through the garbage collector. That means you rarely have to think about freeing ordinary objects. However, some things — such as open files, network connections, database handles, and other operating-system resources — are not fully managed by the runtime. If you forget to release them promptly, they can stay open much longer than you expect. This leads to problems like file-locking errors, network timeouts, and eventually memory leaks.

To solve this, .NET has a pattern built around two pieces:

The

IDisposableinterface, which lets a class signal “I hold on to something that needs explicit cleanup.”The

usingstatement, which makes it easy to clean up such objects automatically.

Understanding these two features will not only make you a better C# programmer but also save you from some of the most common mistakes beginners make with resource management.

The Challenge of Unmanaged Resources

Most ordinary objects in C# — things like strings, lists, dictionaries — live on the managed heap. When you stop referencing them, the garbage collector eventually reclaims the memory for you. You don’t have to do anything.

However, some objects represent things outside the managed heap. Examples include a file that you opened on disk, a network socket, a database connection, or even certain graphics objects. The garbage collector doesn’t know when you’re “done” with them; it only knows when there are no more references to the object. That means if you hold on to such an object longer than necessary, or if the GC simply hasn’t run yet, those external resources stay tied up — sometimes for seconds, sometimes for minutes.

This delay can lead to practical problems. For example, imagine you open a file for writing and then finish your work but never close it. Another part of the program (or another application) might try to open the same file but fail because your program still has it locked. The goal, therefore, is to release these resources as soon as you’re done using them, not just whenever the GC happens to run. That’s where IDisposable and using come in.

Understanding the Two Kinds of using in C#

Before we go deeper, it’s important to clear up a common source of confusion. The word using shows up in two different places in C#, and it does two completely different things. You’ve probably seen lines like these at the top of a C# file:

Common import directives

These are namespace import directives. They run at compile time, not at runtime. They simply tell the compiler where to find the classes you refer to in your code. That way, you can write:

Less typing with the import directive

instead of:

You need to use the fully qualified name without the import directive

This kind of using is purely about convenience for the programmer and has nothing to do with object cleanup. Inside a method or block of code, you’ll see using wrapped around an object:

A different context for the “using” keyword

This is the resource-management using. It tells the compiler to generate code that automatically calls Dispose() on that object as soon as the block ends.

Here’s a quick comparison:

Table showing the different usages of the “using” keyword

A good mental shortcut:

Top of file → “tell the compiler where to look”

Inside code → “clean up when I’m done”

Now that we’ve cleared up this distinction, let’s focus on the resource-management version of using, which works hand-in-hand with IDisposable.

Understanding IDisposable

The IDisposable interface is simple — it defines just one method: Dispose(). If a class implements this interface, it is making a promise: “Before you throw this object away, call Dispose() so I can clean up my resources.”

Many of the classes you use for working with external resources implement this interface. FileStream, StreamReader, SqlConnection, HttpClient — all have a Dispose() method. Calling it tells the object to release file handles, close network connections, free unmanaged memory, and so forth.

The Old Way: Manual Disposal

Before C# added special syntax for this, the recommended pattern was to use a try/finally block. You would create the resource, do your work, and then dispose of it in the finally section to guarantee cleanup even if an exception occurred:

The old way was verbose- we could use a little syntactic sugar here 😏

This works, but it’s clumsy. You have to remember to write the finally block every time, and it makes code harder to read.

The using Statement: A Safer Shortcut

To make things cleaner, C# introduced the using statement.

A using block automatically wraps your code in the equivalent of a try/finally and calls Dispose() for you when the block ends.

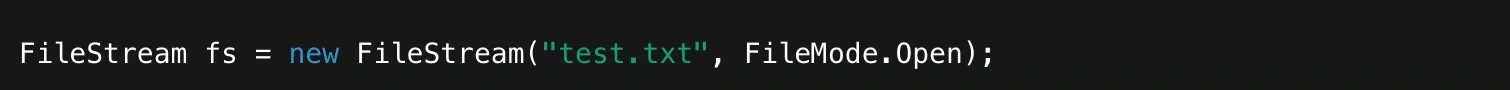

Here’s the same example rewritten with using:

Dispose is called automatically

As soon as execution leaves the using block — whether normally or because of an exception — the Dispose() method is called. This makes your intent clear and removes boilerplate.

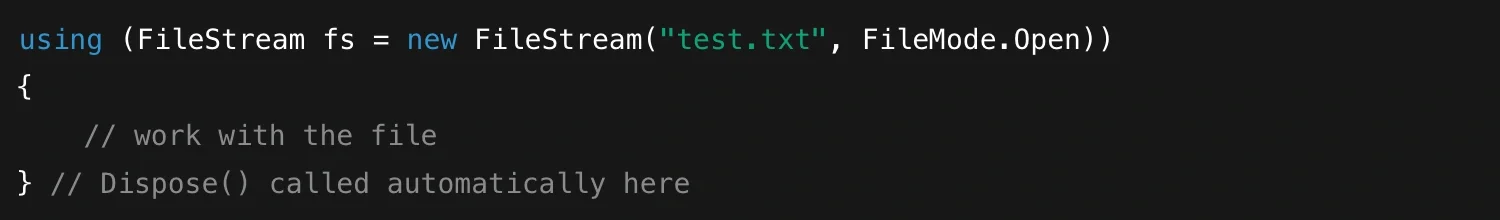

The Modern Shortcut: Using Declarations

C# 8 introduced a more streamlined form called the using declaration. You can declare a disposable object with the using keyword at the start of a scope without adding an extra code block:

Another way, to avoid having to indent subsequent code

This is especially nice in methods where you already have a natural scope and don’t want to indent everything inside a using block.

Both the old-style block and the new declaration do the same thing behind the scenes:

the compiler turns them into a try/finally that calls Dispose().

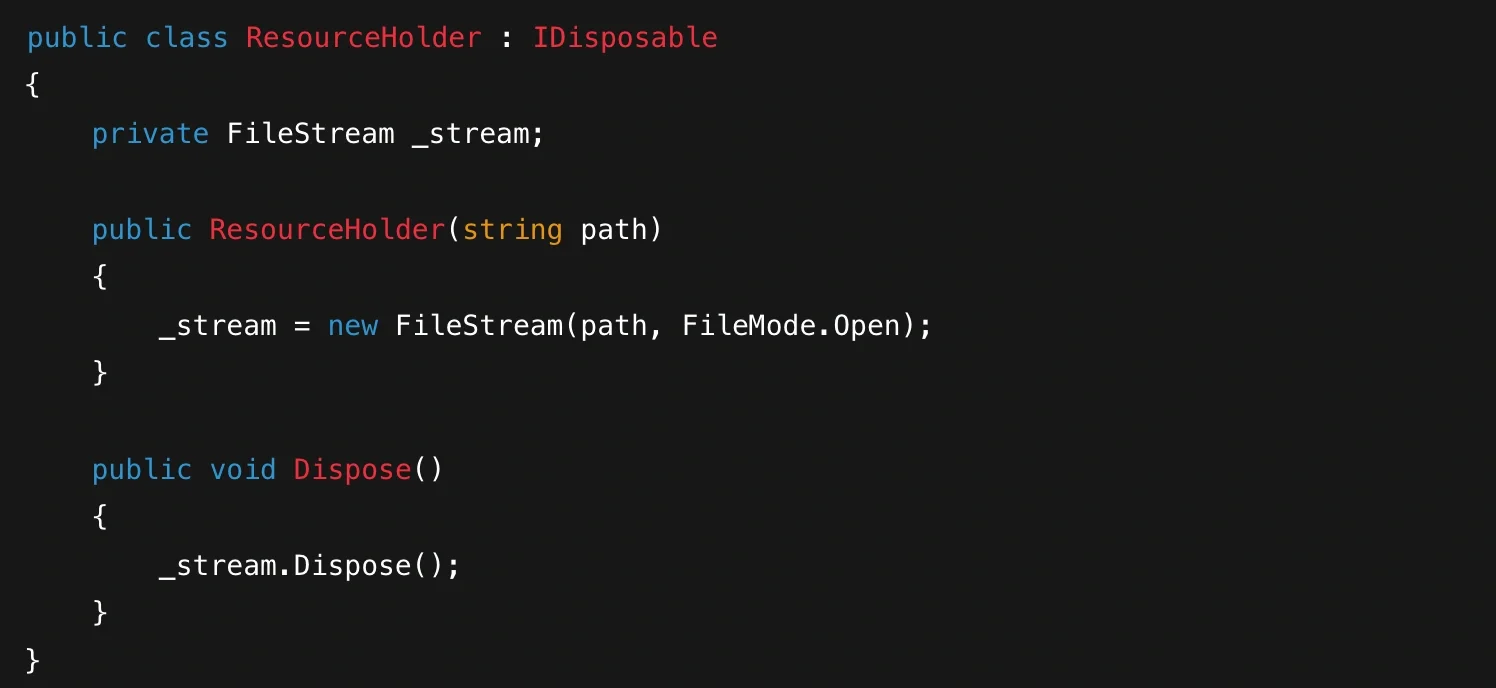

Implementing IDisposable in Your Own Classes

You’ll often use using with built-in classes, but sometimes you’ll need to create your own class that manages resources. Suppose you build a class that opens a file and keeps it open while doing some processing:

Implementing IDisposable in your own classes

Because ResourceHolder implements IDisposable, you can now use it in a using statement:

“using” with your class

This pattern makes your class play nicely with the rest of the .NET ecosystem.

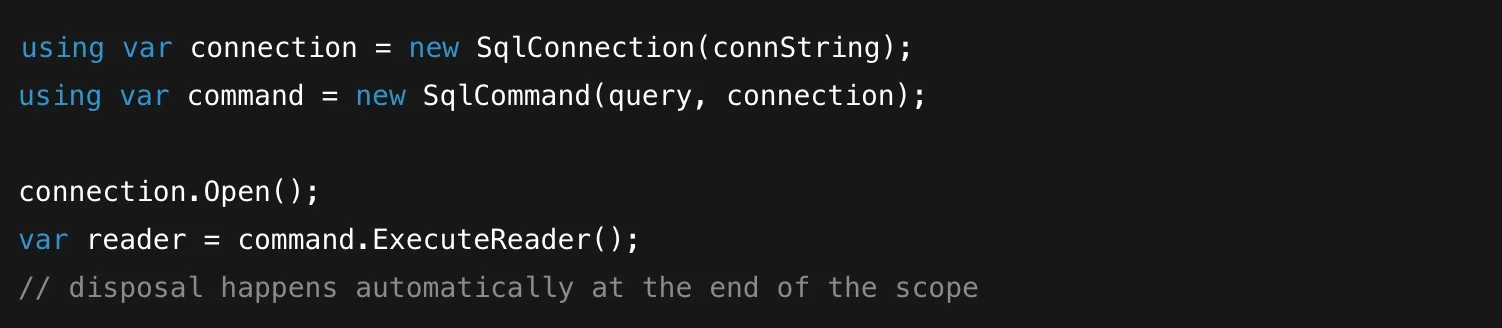

Working with Multiple Resources

It’s common to need several disposable objects at once. For example, when you connect to a database you often need both a SqlConnection and a SqlCommand. You can chain using statements like this:

Chaining using statements

Or, in modern C#:

A more modern way of doing the last example, without having to add braces

This is clean, readable, and ensures that all resources are released promptly.

Asynchronous Disposal

Some resources can clean up more efficiently in an asynchronous manner — for example, when flushing buffers to disk or closing a network stream. C# 8 introduced IAsyncDisposable and the await using syntax to handle this:

Using with await in asynchronous programming

This pattern works the same way as using, but calls DisposeAsync() instead of Dispose(), allowing the cleanup to run without blocking a thread.

Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

Beginners often assume the garbage collector handles everything. While it eventually cleans up memory, it doesn’t know when you’re done with unmanaged resources. Failing to dispose them promptly can cause leaks, performance issues, and locked files. Always prefer using (or await using) whenever you create a disposable object. It’s concise, safe, and communicates your intent clearly.

Another pitfall is disposing of objects too soon or too often. Some classes, such as HttpClient, are meant to be reused rather than created and disposed for each request. Disposing them frequently can actually hurt performance by constantly tearing down and recreating underlying connections. When in doubt, check the documentation for recommended lifetime management.

Finally, if you implement IDisposable in your own classes, make sure you clean up only the resources your class owns. If you also hold unmanaged resources, follow the full dispose pattern with a finalizer to catch cases where the developer forgets to dispose.

Performance Considerations

Calling Dispose() is usually very fast. The main benefit of proper disposal isn’t raw speed but predictability and resource efficiency. You’re telling the runtime and the operating system: “I’m done with this resource; you can reclaim it now.” This reduces memory footprint, avoids contention for file handles or sockets, and often improves the responsiveness of your application.

When working with asynchronous I/O, using DisposeAsync() helps by freeing resources without blocking threads, which is especially valuable in high-throughput server applications.

Conclusion: A Small Keyword with a Big Impact

The using statement might look like a tiny piece of syntax, but it embodies an important programming discipline: deterministic cleanup of resources. By pairing it with the IDisposable interface, C# gives you a clean, reliable way to manage things the garbage collector can’t handle on its own.

For a beginner, the key takeaway is simple: whenever you work with an object that implements IDisposable, wrap it in a using (or await using) block. Doing so keeps your programs safe from subtle bugs, makes your code clearer to others, and teaches you an important principle of resource management that applies in many other languages and frameworks.